Coronavirus: A mental and physical health crisis

Our Head of Child Protection in China discusses the impact of coronavirus

As coronavirus grips the world, our experts are examining what it means for the world's poorest communities, what we can do to slow it down and how we can support health workers, communities, families and children.

By Wing Yan Mak, World Vision China’s Head of Child Protection

Coronavirus is a terrible, deadly disease. It’s killed more than 16,500 people so far, over 3,000 of them in my country, China.

The past few weeks have been terrifying for many of us, even those of us in the aid sector, working hard to deliver much needed equipment and supplies to hospitals and vulnerable families. The people we’re helping include our neighbours, even our own families. It is an unprecedented time.

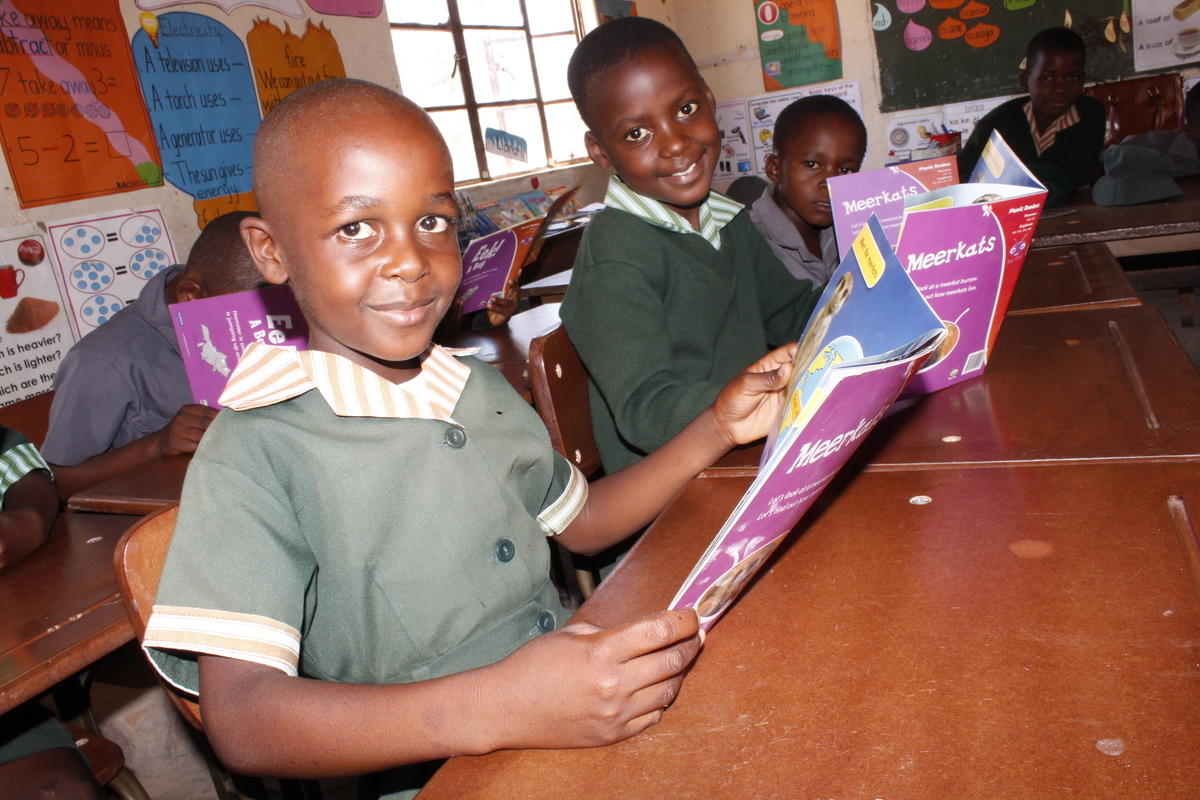

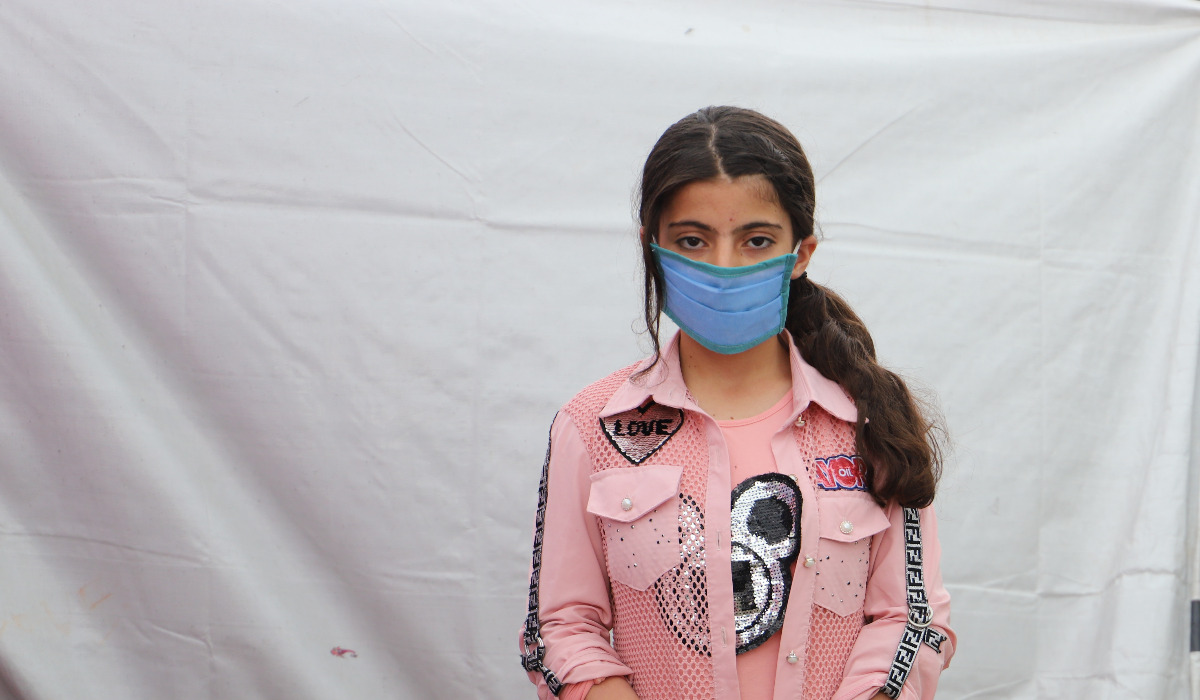

And while children have largely been spared the worst physical impact of the virus, they remain incredibly vulnerable to the secondary impacts of the disease. What happens to children whose parents are falling ill, or die? Or those whose caregivers lose their jobs, meaning that they can’t put food on the table anymore? It was reported in January that a 16-year-old with cerebral palsy died after his father and brother were quarantined, leaving him without care.

What impact is this having on the mental health of an entire generation of children?

We may not know the full extent of this catastrophe for some time, but we already know this: children are suffering.

Feelings of anxiety, mistrust of others and fear of contracting the virus are common. Misinformation and rumours about the growing threat posed by the virus and shortage of daily necessities are worsening the anxiety, and strict restriction of movement – while crucial to slow the spread of the disease – mean that many families are left isolated.

The Chinese Psychology Society found that almost half of all respondents to a survey (42.6 per cent) felt anxious, and out of 5,000 people who participated in a test on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), more than a fifth had obvious symptoms. Children living with stressed parents are likely to share the burden of stress, and are at higher risk of negative coping mechanisms such as violent behaviour and substance abuse.

Children have also told our staff they feel worried about not seeing their friends for a long time – not able to socialise except through social media.

World Vision's response

World Vision China has been responding practically to the coronavirus outbreak for weeks, and plan to reach 1.3 million people. Our staff have been working tirelessly to provide vital medical gear and equipment to fight the spread of Covid-19 and keep communities and health workers safe. We have also already provided 450,000 masks, 28,000 bottles of disinfectant, and 84 sets of critical medical equipment to health workers and communities, while over 50,000 family hygiene packs are ready for distribution to vulnerable families.

But we also want to respond to the psychological needs of families and children. Their mental well-being is as important as their physical health.

Mental health support for children

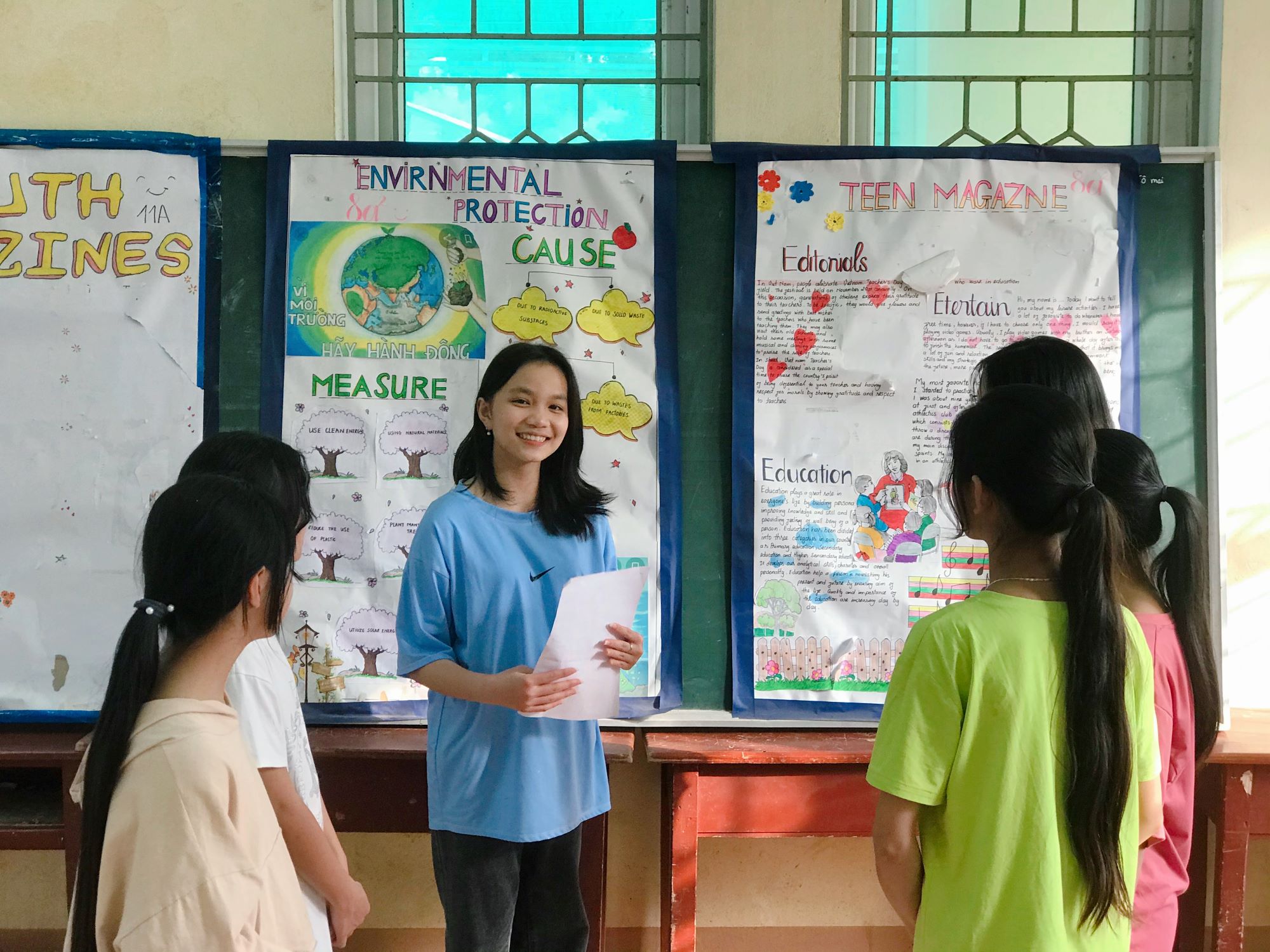

In conjunction with the Institute of Psychology at the Chinese Academy of Science, we’re helping to train teachers, so they can provide quality mental health and psychosocial support to children. We’re teaching them to identify signs of psychological and social distress, including behavioural and emotional problems, and how to care for children who are experiencing stigma as a result of the crisis. Our staff are also training teachers in psychosocial first aid skills and positive coping mechanisms, and launching activities to promote good mental health. We’re also putting systems in place so that children suffering from acute stress are identified and referred to professional counsellors for follow up.

Our work doesn’t stop there, though. We’re also working with social workers – whose role is crucial at a time like this. We’re preparing to offer training in psychosocial support to children and their families, particularly those who have symptoms of trauma after quarantine, separation from loved ones or exposure to severe stressors. Social workers will also be provided assistance in coaching and referral to specialised services, as needed.

To help children who may have been exposed to violence as a result of coronavirus, we’re also working alongside child welfare workers, equipping them to identify child protection threats and work with families and local governments to support those who need it.

These are unprecedented times, but World Vision’s vast experience in dealing with crises all over the world means we’re well-placed to ensure we protect vulnerable children, wherever they live.

Watch our video giving an update on World Vision's work on the ground in China: